Lupine Publishers - Journals of Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Risk Predictive Factors to Convert Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy into Other Procedures by Eldo E Frezza in Lupine Publishers

Introduction

Conclusion

Abstract

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) is nowadays the procedure of choice

for cholecystitis. The intraoperative finding can make

this procedure quite tricky such as dense adhesions at calot’s triangle,

fibrotic and contracted gallbladder, acutely inflamed or

gangrenous gallbladder, cholcystoenteric fistula, etc. There are also

risk factors which make laparoscopic surgery difficult like

old age, male sex, obesity, previous abdominal surgery, thickened

gallbladder wall, distended gallbladder, pericholecystic fluid

collection, impacted stone, etc.

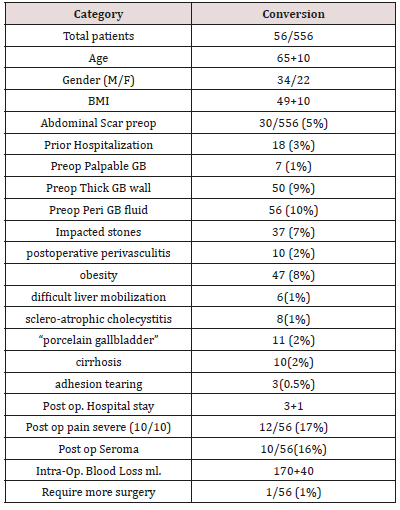

Methods: This is a one cohort retrospective review of patients admitted to the hospital with acute cholecystitis who during LC

were converted to intraoperative cholecystostomy tube placement (CCT) or to open cholecystectomy (OC). Preoperative risk factors

to predict difficult cholecystectomy were evaluated.

Results: Medical records were reviewed retrospectively from

January 2010 through December 2016. IRB approval was

obtained. LC was performed in 556 cases between 2010-2016, with 56 (10%)

conversion: 39 CCT and 17 OC. The highest reason

for conversion are Perioperative fluid around the gallbladder before

surgery on the ultrasound (10%), preoperative thickness of

the gallbladder (9%), Impacted stones (7%) are the predicting factor

that have more changes to turn the LC into a different surgical

approach. These three parameters are followed by Prior Hospitalization

(3%) and presence of abdominal scar (5%). Essential

factors to make a problematic surgery were postoperative perivasculitis

(2%), obesity (8%), difficult liver mobilization (1%), acute

and scleroatrophic cholecystitis (1%), “porcelain gallbladder” (2%).

Causes of bleeding during our operation were: cirrhosis (2%),

accidental adhesion tearing (0.5%) (Table 1).

Conclusion: Problematic LC can be diagnoses before the surgery and make the OR team ready for different surgical approach.

Keywords: Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy; Open Cholecystectomy; Cholecystostomy Tube; Difficult Cholecystectomy; Predictive

Factors for Difficult Surgery.

Introduction

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) is nowadays the procedure

of choice for cholecystitis [1]. The intraoperative finding can make

this procedure quite tricky such as dense adhesions at calot’s triangle,

fibrotic and contracted gallbladder, acutely inflamed or gangrenous

gallbladder, cholcystoenteric fistula, etc. [2]. There are also risk

factors which make laparoscopic surgery difficult like old age, male

sex, obesity, previous abdominal surgery, thickened gallbladder

wall, distended gallbladder, pericholecystic fluid collection,

impacted stone, etc. [3]. A cholecystostomy is an opening made in the

gallbladder, to place a tube for drainage. John Stough Bobbs, in 1867,

was the first to described it [4,5]. It has been used in 1) person is ill,

and 2) to defer cholecystectomy [6]. Todd Baron and Mark Topazian

in 2007 place the first percutaneous Cholecustostomy Tube using

ultrasound guidance [7]. The role of Cholecystostomy tube (CCT) is

controversial in current surgical practice [8]. In critically ill patients,

cholecystostomy tubes should remain in place until the patient is

deemed medically suitable to undergo cholecystectomy. Removal

of the cholecystostomy tube without subsequent cholecystectomy

was reported associated with a high incidence of recurrences. [9]

Attempts to predict intraoperative difficulties was described and

included, palpable gallbladder, pericholecystic fluid, male more

than female incidence, etc. [11], but still is not an 100% given all

patients are different. Technical and tactical solutions to deal with

complicated cholecystitis surgery were reported [10] but cannot

be always applicable. Our study is based on the assumption that

difficulty cholecystectomy can be defined before the surgery and

give the opportunity to the surgical team to prepare for alternate

surgeries option like Open Cholecystectomy (OC) or intraoperative

Cholecystostomy Tube placement (CTT).

Methods

This is a retrospective review of patients admitted to the

hospital who were diagnosed with acute cholecystitis who

underwent an initial laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. The study

was designed to find those patients who were converted in other

surgery than LLC and check if the preoperative work out was

predictive of failure of LLC. The Cohort taken in consideration were

those who converted into Cholecystostomy Tube Placement (CCT)

or to open cholecystectomy (OC). Medical records were reviewed

for demographic data, diagnoses, imaging, complications, and

outcomes: from January 2010 through December 2016 from the

same surgeon. IRB approval was obtained.

a) Inclusion Criteria: All patients who underwent LC from

January 2010 to December 2016 were included in the study.

b) Exclusion Criteria:

i. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy performed with other

laparoscopic intervention in the same setting.

ii. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy with Common Bile Duct

(CBD) exploration.

iii. Absolute contraindications to LC like cardiovascular,

pulmonary disease, coagulopathies, and end-stage liver disease.

Demographic symptoms sings of presentations were evaluated

to find if those were impacting on our surgeries and addresses

the activities of the cholecystectomy. The evaluated risk were

the following: history os hospitalization, palpable gallbladder,

thicken gallbladder, peri-cholecystitis fluid, impacted stones at

the neck, abdominal scar. The characteristic of the patients was

reported in Table 1.

Pre And Intraoperative

A detailed proforma was in place before the surgery to record

information regarding patient history, physical examination,

laboratory parameters, ultrasonography (USG) findings and intraoperative

details.

Operative Technique

After obtaining an informed consent including an option for CCT

and OC the patient was taken to the operating room placed under

general anesthesia and prep in the usual fashion. The first incision

was done in the left upper quadrant with a knife and a trocar, and a

camera was advanced through the tissue under direct vision. Once

in the abdomen, we obtained a pneumoperitoneum of 15mmHg.

We place 2 five mm trocars in the right upper quadrant, one at the

level of the belly button of 5 mm. The initial trocar was switched to

a 12mm trocars. Evaluation of the Right upper quadrant and the

gallbladder was made.

Critical Factors

The crititical factor evaluated to continue the LC or turned into

CCT or OC: 1) a change of the color of the gallbladder (green etc),

2) multiple adhesion which could not be taken out, 3) inability to

grab the gallbladder after aspirating with the needle, 4) failure to

see after the body of the gallbladder and define the neck of the

gallbladder without good vision of the area of the common bile

duct.

CCT

The fundus of the gallbladder was open with the Bovie. The

fluid was aspirated, and the stones inside in the gallbladder were

taken out by grasping with a laparoscopic Babcock after all the

stones were cleaned and placed one by one in a separate bag

inserted in the abdomen. The bag was closed. We then whased the

gallbladder with saline, which also helps to mobilize hidden stones.

The camera was then advance inside the gallbladder and evaluated

from inside visualize the cystic duct. Once we know they there no

other stones obstructing, a 2/0 silk purse string was placed at the

fundus opening. With a separate incision, a Foley 18 French was

inserted in the abdomen and the tip placed inside the gallbladder.

The purse string was tied, and the balloon of the Foley was filled

with seven ml. of saline. A Jackson Prat was placed at the liver fossa

and secure with a 2/0 nylon to the skin. Same suture was used to

secure the CCT to the skin. as we did to achieve the Foley now new

cholecystostomy tube. The CCT was connected to a Foley bag and

left on gravity. Given the difficult to have a real CCT, we usually use

a Foley 18 French as CCT tube. We wash the abdomen and close

the trocars with 4/0 monocryl and dermabond. After surgery,

the patient was allowed to advance the diet and walk. Most of the

patients were discharged within 36 hours with home health.

OC

If the CCT was not possible with a knife, we made a subcostal

incision. The incision was then taken down with the bouvie while

separating the muscle. Once in the abdomen, we close the gas

insufflation. Few laps were placed on the stomach, duodenum

and colon side. The gallbladder was grasped with a kelly clamp

and dissected with bouvie from the liver. Once at the neck of the

gallbladder was visualized the artery and the cystic duct, were

dissected either between clips or with vascular staplers. Jackson

Prat ten French drainage was placed in the liver fossa and secure to

the skin. The wound was closed in layers with one vycril and stapler

for the skin. The patient was allowed fluid, they were placed on PCA

pump and discharge home with home health care within 4 days.

Post OP Treatment of the CCT

The tube was left on biliary bag drainage, Cholangiogram is

ordered between week 4 and 6. If no stones were found from the

cholangiogram the tube was pulled out in the office otherwise redo

surgery was scheduled.

Results

556 cases were performed between 2010-2016 by the same

surgeon, Total 56 patients (10%) who match our criteria were

converted: 39 CCT and 17 OC. The surgery was performed by the

same surgeon in different hospitals. Mean intraoperative time

was 51 ± 26 min (range 27–77min) in CCT and 53 ± 28min (range

25–81 min) in OC. Postoperative hospital stay was 1.4 ± 0.4 days

in CCT and 4 ± 1 in OC (p< 0.05). The operative data, time bleeding

and postoperative hospital stay, seromas incidence were collected

and reported in Table 1. The following comorbidities were founded:

cardiovascular disease (20 patients), respiratory failure (10

patients). At 30 days, the morbidity associated with the CCT itself

was 4% while OC was 70%. Of the patients who underwent CCT

only one (10%) underwent LC after 30 days. Perioperative fluid

around the gallbladder before surgery on the ultrasound (10%),

preoperative thickness of the gallbladder (9%), Impacted stones

(7%) are the predicting factor that have more changes to turn the

LC into a different surgical approach. These three parameters are

followed by Prior Hospitalization (3%) and presence of abdominal

scar (5%) (Table 1). Essential factors to make a problematic surgery

were: postoperative perivasculitis (2%), obesity (8%), difficult

liver mobilization (1%), acute and scleroatrophic cholecystitis

(1%), “porcelain gallbladder” (2%). Causes of bleeding during our

operation were: cirrhosis (2%), accidental adhesion tearing (0.5%)

(Table 1).

Discussion

With the help of accurate prediction, the high-risk patient may

be informed beforehand regarding probability of conversion to OC

or CCT. This discuss will also help the surgeon and the OR team to

prepare the alternative surgeries. Surgeons should be aware of the

possible complications that may arise in high-risk patients.

Risk Predictors Factors

Male sex makes surgery difficult as being reported in studies

[10-12]. Conversion rate and significantly higher mortality [13,8]

and found to be a significant factor. Subtotal cholecystectomy,

antegrade and fundus first techniques which is now being

more commonly done during LC were associated with lower

complications and conversion rate. Other risk factors for

difficulty surgery are reported as increased age, acute and thick

wall chronic cholecystitis, wide and short cystic duct, cholecyst

digestive fistula, previous upper abdominal surgery, obesity,

liver cirrhosis, anatomic variation, cholangiocarcinoma, and low

surgeon’s caseload [14]. Although decompression and drainage

of the gallbladder through a radiological placed cholecystostomy

tube may be used as a temporary treatment of acute cholecystitis

in ill population, there is still some debate about the management

of the tube and the subsequent need for a cholecystectomy. Other

authors reported 105 patients, 12 (11.4%) required conversion

to open cholecystectomy. They pointed out that their significant

predictors of conversion were body mass index> 30Kg/m2, male

gender, history of acute cholecystitis or acute pancreatitis, the

recent history of upper abdominal surgery, and gallbladder wall

thickness exceeding 3mm [15]. Thickened gallbladder wall is

an ultrasonographic finding of acute cholecystitis, and it was a

significant factor in previous studies [16-18]. James Majeski [16],

showed that a preoperative gallbladder ultrasound evaluation with

a thick gallbladder wall (>3mm) and calculi, is a clinical warning for

a problematic laparoscopic cholecystectomy procedure which may

require conversion to an open cholecystectomy procedure [19].

But Carmody concluded that detailed preoperative ultrasound

evaluation of the gallbladder in patients destined for laparoscopic

cholecystectomy is of little value in screening for difficult or

unsuitable cases. They found that there were no ultrasound

features that can differentiate between the unsuccessful, confusing,

or uneventful laparoscopic cholecystectomy [20]. In our study

thickened gallbladder wall was present in all patients and outcome

was found to be dependent on this variable by chi-square test (p

= 0.001), and logistic regression analysis also ascertained the

significance of this factor for prediction (p = 0.005). Pericholecystic

fluid is an ultrasonographic finding of acute cholecystitis. This

was found to be a significant factor in our study (p = 0.939), as

well as palpable gallbladder (p = 0.05). Therefore, we agree with

Randhawa [21] who also reported that presence of palpable

gallbladder has a significant bearing on define difficult surgery.

Difficulty in gallbladder grasping was associated significantly with

the conversion. A distended gallbladder or a gallbladder filled with

stones is not easily grasped because it tends to slip away. Presence

of inflammation around the gallbladder makes the wall friable

and edematous, thus posing problems. These data were reported

by Singh [22] who also found a significant association between

difficulties in grasping a distended gallbladder and pericholecystic

inflammation. Lal [23] have identified that presence of large stones

in the gallbladder neck leads to distention and difficulty in grasping.

Cholecystostomy

Percutaneous Cholecystectomy (PCCT) is primarily indicated

for accessing the gallbladder to manage cholecystitis or to serve

as a portal to remove or dissolve gallstones [24,25]. In the current

literature and clinical practice, surgeon and internal medicine

physician continue to recommend PCCT as an alternative to surgical

cholecystectomy in patients with acute cholecystitis deemed poor

surgical candidates. This trend is mainly based on retrospective

studies [24,25,9] and anecdotal clinical experience, which result

in an inconsistent and unsupported utilization of PCCT. The

recommendation of PCCT over surgical alternatives will continue to

be based mostly on clinical intuition until randomized, controlled

trials answer a series of questions regarding the treatment of acute

cholecystitis [8]. If surgical options under general anesthesia can

be avoided by a fast, simple, low-risk procedure under conscious

sedation in any patient, it stands to reason that that procedure

should become the new primary treatment option. Controversy

and confusion over the application of PCCT raise a critical question:

Does the existing, albeit insufficient, literature support the potential

use of PCCT as a first-line and potentially definitive therapy for any

cases of acute cholecystitis? PCCT should be still considered in a

critical ill patient who cannot stand general anesthesia. Some other

authors were close to our concept and tried to dissolve the stones

to avoid another surgery by placing CCT laparoscopically.

Authors have employed the cholecystostomy tract to facilitate

removal of gallstones by basket extraction [26] dissolution

with bile acids, and destruction and retrieval with shock-wave

lithotripsy [27,28,29]. Retrospective studies have demonstrated

a gallstone recurrence rate of ∼10 to 30% per year and a

symptomatic recurrence rate requiring repeat treatment of

∼6 to 18% per year. Stone removal can be repeated as needed,

but the high rate of symptomatic recurrence and the risks and

consequences of recurrent acute cholecystitis may limit the future

of this option as a definitive treatment. With nowadays improved

laparoscopic technique the conversion rate should be minimal in

our experience is only 10%. The highest reason for conversion are

Perioperative fluid around the gallbladder before surgery on the

ultrasound (10%), preoperative thickness of the gallbladder (9%),

Impacted stones (7%) are the predicting factor that have more

changes to turn the LC into a different surgical approach. These

three parameters are followed by Prior Hospitalization (3%) and

presence of abdominal scar (5%) (Table 1) and made high risk

for performing another surgery but LLC. Other factor whoch can

predict problematic surgery were: postoperative perivasculitis

(2%), obesity (8%), difficult liver mobilization (1%), acute and

scleroatrophic cholecystitis (1%), “porcelain gallbladder” (2%).

Causes of bleeding during our operation were: cirrhosis (2%),

accidental adhesion tearing (0.5%) (Table 1).

Conclusion

Problematic LC can be diagnoses before the surgery and make

the OR team ready for different surgical approach. Conversion

should be kept less than 20% of the cases in out experience was

10%. PCCT should be still considered in a critically ill patient who

cannot stand general anesthesia.

For More information

For more Lupine Publishers Open Access Journals Please visit our website: https://lupinepublishersgroup.com/

For more Open Access Journals Please visit our Lupine Publishers

Comments

Post a Comment